Tales from Cornwall’s wild side

Bude, Cornwall

by Sarah Shuckburgh

Bude’s modest exterior hides a

bizarre history involving a dotty vicar and a famous

inventor, discovers Sarah Shuckburgh.

I had

heard of Gurney stoves, and always assumed that harvest

festivals were an ancient tradition, but until this week, I

had no idea that both were invented by eccentric Cornishmen

living on a remote stretch of the county’s wildest and most

dramatic shore.

The Cornish have always seen themselves as separate from the

English, and the county is indeed almost an island - the sea

or the river Tamar surround all but two miles of its

borders. For Anglo-Saxons, these two miles, in the parish of

Morwenstow, provided an important crossing point, but today

they form one of the most beautiful and unspoilt parts of

Britain. Here, narrow lanes with high stone walls are dotted

with primroses in spring and foxgloves in summer, and lead

into steep wooded valleys and over rolling maritime

grassland. The coast is rugged and treacherous, with

spectacular rock formations - barrel-shaped folds of rock,

diagonal strata, zigzag chevron patterns, stripy layers of

pale sandstone and dark siltstone.

The

Cornish side of my family has farmed on this coast for 200

years, and the non-Cornish side has been coming here on

holiday since 1900, but I had no idea that harvest festivals

were invented in the 19th century at Morwenstow church.

Stephen Hawker arrived in 1834, Morwenstow’s first vicar for

more than a century. He devoted his life to converting local

smugglers, wreckers, looters and dissenters into a

congregation of lifesavers, who warned ships away from the

rocks, gave drowned sailors Christian burials – and

celebrated local harvests.

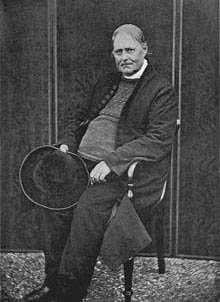

Parson Hawker was delightfully dotty, dressing in red coat,

pink fez and yellow horse-blanket poncho, posing on rocks in

mermaid costume, inviting his nine cats to church services

(excommunicating them if they moused on a Sunday) and taking

his pet pig for walks. He had two happy marriages, at 19 to

his 40-year-old godmother, and then at 60 to a girl of 20. Parson Hawker was delightfully dotty, dressing in red coat,

pink fez and yellow horse-blanket poncho, posing on rocks in

mermaid costume, inviting his nine cats to church services

(excommunicating them if they moused on a Sunday) and taking

his pet pig for walks. He had two happy marriages, at 19 to

his 40-year-old godmother, and then at 60 to a girl of 20.

From

Morwenstow churchyard and Hawker’s turreted rectory, I

strolled through a steep-sided valley, gouged during the Ice

Age, and joined the coast footpath. Far below me, Atlantic

waves churned and crashed against the rocks. Farther out,

swirls of glittering blue-green faded to a fuzzy horizon

that my Cornish grandmother would say heralds fine weather.

Soon I reached the National Trust’s smallest property,

Hawker’s Hut, perched on a cliff and built entirely of

driftwood. Here Hawker composed sermons, watched for

shipwrecks and wrote romantic poems such as The Song of the

Western Men, now adopted as the Cornish national anthem. He

also smoked opium and conversed with Saint Morwenna, the

fifth-century princess who built a church with her own

hands, and gave her name to the parish.

The next day, the wind got up and the incoming tide looked

perfect for surfing. I headed for Bude’s beautiful

Summerleaze beach with my ancient plywood surfboard.

Old-fashioned as my board my look, it is streamlined

compared to the coffin-like box on which my grandmother rode

the waves before the First World War. The next day, the wind got up and the incoming tide looked

perfect for surfing. I headed for Bude’s beautiful

Summerleaze beach with my ancient plywood surfboard.

Old-fashioned as my board my look, it is streamlined

compared to the coffin-like box on which my grandmother rode

the waves before the First World War.

To warm

up after my swim, I visited Bude Castle, built on

Summerleaze sandhills by Sir Goldsworthy Gurney. Few have

heard of this Cornish genius, a contemporary of Parson

Hawker (they both died in 1875). To prove that it was

possible to build on shifting sand, Gurney designed a castle

on a specially-invented concrete base – and it is still

standing 178 years later.

Sir Goldsworthy Gurney was an extraordinary polymath –

architect, agriculturalist, surgeon, scientist, pianist and

prolific inventor - but he veered between success and

bankruptcy, and he regularly failed to gain credit for his

inventions. Gurney’s oxyhydrogen blowpipe, which produced

limelight, was used for theatres by Drummond, and became

known as Drummond light. In 1829, his Gurney Drag steam-carriage travelled by road from London to Melksham,

averaging 15 miles per hour – the first long-distance

steam-powered journey - but the government backed

Stephenson’s Rocket and imposed crippling road-tolls.

Gurney’s ingenious plans to ventilate parliament by sucking

sewage smells up through Big Ben were never implemented.

Gurney’s best-known invention during his lifetime was Bude

light – a mix of lime and magnesium so bright that one lamp,

reflected through prisms and mirrors, illuminated his entire

castle. These lights soon lit Trafalgar Square and Pall

Mall, and three Bude lights replaced 280 candles in the

Houses of Parliament, lasting until electricity was

installed 60 years later. Sir Goldsworthy’s system of

flashing lighthouses is still in use, and his Gurney stoves

survive in several cathedrals to this day. Sir Goldsworthy

Gurney, knighted in old age by Queen Victoria, invented

blastpipes, steam engines, mine ventilation, fire

extinguishers, musical instruments, heating, lighthouse

flashes, electric telegraph and theatrical limelight, but

was never in the limelight himself. Sir Goldsworthy Gurney was an extraordinary polymath –

architect, agriculturalist, surgeon, scientist, pianist and

prolific inventor - but he veered between success and

bankruptcy, and he regularly failed to gain credit for his

inventions. Gurney’s oxyhydrogen blowpipe, which produced

limelight, was used for theatres by Drummond, and became

known as Drummond light. In 1829, his Gurney Drag steam-carriage travelled by road from London to Melksham,

averaging 15 miles per hour – the first long-distance

steam-powered journey - but the government backed

Stephenson’s Rocket and imposed crippling road-tolls.

Gurney’s ingenious plans to ventilate parliament by sucking

sewage smells up through Big Ben were never implemented.

Gurney’s best-known invention during his lifetime was Bude

light – a mix of lime and magnesium so bright that one lamp,

reflected through prisms and mirrors, illuminated his entire

castle. These lights soon lit Trafalgar Square and Pall

Mall, and three Bude lights replaced 280 candles in the

Houses of Parliament, lasting until electricity was

installed 60 years later. Sir Goldsworthy’s system of

flashing lighthouses is still in use, and his Gurney stoves

survive in several cathedrals to this day. Sir Goldsworthy

Gurney, knighted in old age by Queen Victoria, invented

blastpipes, steam engines, mine ventilation, fire

extinguishers, musical instruments, heating, lighthouse

flashes, electric telegraph and theatrical limelight, but

was never in the limelight himself.

Next,

I explored the Bude Canal, which has been dredged and

restored to make a lovely inland walk. Away from the wild

coast, Bude’s hinterland is calm and peaceful. Sir

Goldsworthy contributed to early designs for the canal, a

revolutionary project to link the Bristol and English

Channels via the river Tamar. The canal never reached the

Tamar’s navigable stretches, but was a superb feat of

engineering with sea locks and basins, a breakwater to

protect the canal from the sea, and six sloping stretches of

canal powered with steam and a unique system of

counterbalanced buckets, each containing 15 tons of water.

Today, the canal’s nature reserve contains Cornwall’s

largest reed beds, home to otters, dormice, and a host of

rare birds and plants. Much of the surrounding countryside

is designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

While Parson Hawker and Goldsworthy Gurney were living their

extraordinary lives, and my Cornish relations were farming,

Bude turned from a fishing harbour and small port into a

fashionable Victorian seaside resort. In 1847, Tennyson

visited this romantic Watering Place of the West and was

inspired to write his Cornish Idylls of the King. Later, the

Atlantic Coast Express railway brought my non-Cornish

relations and other well-heeled visitors direct from London,

and Bude’s attractions included a sea pool, art deco cinema,

three golf courses, and a series of huge hotels.

However, Bude’s economic decline had begun, with

agricultural depression, the First World War, mass

emigration to the New World, and, in the 1930s, the closure

of the canal, lifeboat station and port. A final blow came

with the closure of the railway, in 1966.

Bude today may have lost its classy clientele, but it is a

friendly, low-key little town filled with the mouthwatering

aroma of hot pasties. Summerleaze beach is a beautiful sweep

of fine sand, with fishing boats pulled up on the tideline,

children playing with buckets and spades, and wet-suited

surfers riding the rolling waves. Bude today may have lost its classy clientele, but it is a

friendly, low-key little town filled with the mouthwatering

aroma of hot pasties. Summerleaze beach is a beautiful sweep

of fine sand, with fishing boats pulled up on the tideline,

children playing with buckets and spades, and wet-suited

surfers riding the rolling waves.

As gulls squawked overhead, I wandered past whitewashed

cottages with grey slate roofs, along modest terraces of

pebbledash and palm trees, and into small locally-owned

shops. I stopped for elevenses at the Falcon Hotel,

established in 1798 as an inn for sea captains. The waitress

confided proudly that Tennyson broke his ankle here in 1847.

Chapel Rock, on the harbour breakwater, is all that remains

from the days when Bude was just a chapel on a rock, where a

bede, or holy man, lit lamps to guide ships in from

Cornwall’s wildest and most treacherous coast. But today the

town is taking renewed pride in its unique cultural and

natural heritage.

Sir Goldsworthy Gurney’s eccentric castle-built-on-sand has

been restored, and now houses an excellent museum, and a

restaurant where I had lunch. Over coffee, I read one of

Parson Hawker’s bloodthirsty ballads - Croon from Hennacliff

- about shipwrecked bodies washing up at Bude. The next time

I go to a harvest festival, or visit a warm cathedral, I

shall remember these two inspired Cornishmen, and the

beautiful landscape that was their home.

First published by the Telegraph

©SarahShuckburgh |