Return to Normandy Return to Normandy

D-Day Beaches, Normandy

by Sarah Shuckburgh

Sir David Willcocks shows his

daughter, Sarah Shuckburgh, the hillside where, 60 years

ago, he fought in the fiercest battle of the D-Day

campaign.

Behind a mossy stone wall, cider apples ripen in a small

orchard. A dusty cart track disappears between fields of

rustling, waist-high corn towards a distant hamlet. Larks

sing in a cloudless sky. It is almost impossible to imagine

the battle fought here nearly 60 years ago, a few days after

D-Day, that would be remembered as the fiercest and most

costly of the Normandy campaign.

My father, (now Sir) David Willcocks, was there as a

24-year-old intelligence officer (43rd Wessex, 214 Brigade,

Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry), but until now I have

never heard him talk about Hill 112, nor of the events that

led to his winning the Military Cross.

Just once, on a summer's day in 1964, as we drove through

Normandy on our way to a family holiday, did he broach the

subject, when he suggested a walk on the hill where he had

fought 20 years before. I was 13. The outing sounded boring,

and I refused to get out of the car. The rest of the family

set off and were gone for an age. When they got back, I was

shocked to see tears in my father's eyes. My sister and

brothers were subdued, and I knew I had missed something

important. I have often thought about that day, and wondered

what I might have learnt about my father had I not been

sulking.

Forty years on, reading about other veterans' plans to visit

battlefields, I suggest that we return to Normandy.

At first my father is reluctant. Since the war, he has

devoted his life to music, as choirmaster, conductor,

composer and director of the Royal College of Music. His

recordings include many with the choir of King's College,

Cambridge, where he was Director of Music for 16 years, and

with The Bach Choir, which he conducted for 38 years. He

still tours the world as a choral conductor and, at 84, his

extraordinary stamina is undiminished. He is not someone who

looks back.

He tells me Normandy will have changed completely. He won't

remember anything. I wouldn't find it interesting. And

anyway his schedule of concerts means that he has no free

time for months. But at last he agrees, and our expedition

is inked into his diary.

And now here we are, my father and mother, my sister and I,

checking into a quiet hotel in the Bocage, a region of

Calvados with sunken lanes and thick hedges, just inland

from Arromanches-les-Bains. Later, we walk along the cliff

towards Gold Beach, where my father's battalion landed on

June 22, 1944, when the sea was so rough that the soldiers

had to jump into chest-deep water and wade ashore, carrying

weapons - and bicycles - over their heads. Precious items,

such as photographs, were stowed under helmets. My father

was one of over two million men to land in Normandy that

summer.

"By the time we arrived, the beach had been made safe, with

mines cleared from a marked area of sand. We followed signs

saying "43rd Wessex This Way", past deserted concrete

pillboxes and over the sand dunes to an assembly point in a

trampled cornfield. What I remember above all is the stench

of rotting cattle and gunpowder. Most of the dead soldiers

had been buried, but there were dead animals everywhere."

My father is by nature cheerful, but next morning, I see an

unfamiliar, introspective side of his character. In the

medieval centre of Bayeux, weighty volumes catalogue the

name, rank and burial place of thousands of soldiers killed

here in 1944. My father, ashen-faced, searches the grim

pages. "So many of my friends died," he murmurs.

We drive first to the war cemetery on the outskirts of

Bayeux. Here, heart-breaking ranks of headstones gleam in

the sunshine. Roses, lavender and other colourful flowers

bloom over each grave. The grass seems impossibly green

and trim, the stone an ethereal white. Among many

stone-carved Wessex wyverns and Cornish coronets lies the

grave of Lt-Col Atherton. My father stands, sombre and

drawn, silently remembering, as bees buzz eagerly among

the flowers at his feet.

"Jack Atherton was my CO, and as his intelligence officer, I

knew him very well. He was a wonderful man. He was killed on

the first day of action." Nearby lies Major Perceval Coode.

"He died the day after Atherton. He was popular with

everyone, and a great friend of mine. At the time, you just

say `Oh dear, old Perceval's caught it.' There's no time for

emotion.

"I'd never seen a dead body before I arrived in Normandy,

but here corpses were lying everywhere you looked. When we

could, we'd dig a grave and mark the spot with a wooden

cross. You'd make a mental note to write to the widow when

you got a chance."

The next cemetery, in fields near the hamlet of St Manvieu,

is smaller and even more poignant. In the corner of its

hauntingly beautiful garden, my father finds the grave of

Captain Basil Aimers.

"I'd served with Basil since I joined the battalion in 1941.

He was an Irishman, a lovely chap, always cheerful. We

played a lot of bridge together. He often talked about his

girlfriend, Rosemary, and after he was killed, she wrote to

his mother regularly until his mother's death many years

later. I know Rosemary still thinks about him." "I'd served with Basil since I joined the battalion in 1941.

He was an Irishman, a lovely chap, always cheerful. We

played a lot of bridge together. He often talked about his

girlfriend, Rosemary, and after he was killed, she wrote to

his mother regularly until his mother's death many years

later. I know Rosemary still thinks about him."

At Banneville-la-Campagne are another 2,000 graves,

including that of my father's second CO, Lt-Col James. In a

small chapel, my father signs the Book of Remembrance and I

feel a lump in my throat as I read the other inscriptions.

"I found you at last, Dad," writes one visitor. "Never

forgotten, my dearest husband," writes another. "I took 60

years to come, but here I am, brother," says one, from

Australia.

The next day, unfolding yellowing War Office maps retrieved

from my parents' attic, we drive between hedgerows strewn

with wild flowers, and past sunny pastures where black and

white cows graze peacefully, to the village where my father

first saw action.

"We started the advance towards Cheux at two in the morning,

in pouring rain," he tells us. "The roads and fields were

sodden and muddy, and we finally jettisoned the useless

bicycles we'd carried ashore at Arromanches and lugged all

the way from the coast. Everything was chaotic. Our

anti-tank guns and other vehicles got held up in the narrow

sunken lanes, and we arrived in Cheux without them. The

troops we were meant to replace had withdrawn too soon -

before we got there - so the village was back in German

hands. It was my first experience of the confusion of real

war."

As Intelligence Officer, my father had to report to the CO

on all four companies in the battalion. "I was visiting the

orchard where one of our companies was based, when I heard

some tanks rumbling towards me," remembers my father. "I

realised they were too big to be British. I jumped into a

shallow ditch with another officer, Hugh Jobson, and we

waited as six Panther tanks thundered down. One halted right

above our heads - the giant caterpillar tracks were either

side of us, not two feet away. German tanks were bigger and

more resilient than our Sherman tanks. Shells just bounced

off them like ping-pong balls. After what seemed like an

age, the tanks rolled on towards battalion headquarters."

What followed on that day made the 5th DCLI famous along the

entire front - in their first half hour of action, with only

20 killed or wounded, the battalion destroyed five Panther

tanks. To knock out one was a considerable achievement. To

get five, manned by SS troops, was extraordinary. But among

the dead in those first 24 hours were Atherton and Coode,

the friends whose graves we had visited that morning.

Having regained and held Cheux for three days, 214 Brigade's

next task was to push on to Colleville, a strategically

placed hamlet a mile to the south. The countryside here is

gently undulating, but the thick hedgerows and deeply rutted

lanes hampered the movement of tanks and artillery. Ripening

cornfields provided cover for snipers, and the walled farms

and compact villages of Calvados favoured defence. The

infantry divisions inched forward, bitterly contesting each

field and hedgerow.

"Operation Jupiter was planned by Montgomery to draw German

forces towards Caen, and allow American troops to break out

to the south and then swing eastwards with less resistance,"

my father explains. "More and more German forces were being

brought in, and by this time we were facing seven Panzer

divisions. We were in the Colleville area for three days,

under constant bombardment."

The battalion's next orders were to occupy Fontaine

Etoupefour, a village near the River Odon. "I'll never

forget the terrifying walk down the railway line," my father

says. "We took all night to get there, in pitch darkness,

stepping over fallen telegraph poles, tangled cables and

twisted rails, and stumbling into craters, with shells

exploding all around. You didn't know where the next one

would fall." The battalion's next orders were to occupy Fontaine

Etoupefour, a village near the River Odon. "I'll never

forget the terrifying walk down the railway line," my father

says. "We took all night to get there, in pitch darkness,

stepping over fallen telegraph poles, tangled cables and

twisted rails, and stumbling into craters, with shells

exploding all around. You didn't know where the next one

would fall."

We look at the army map. "It's only three miles," exclaims

my father in surprise. "But it felt like 20. It was

incredibly frightening. We crossed the Odon, and crept on as

far as Fontaine Etoupefour by moonlight. We dug slits, and

spent the next day hiding there, behind enemy lines, with

German patrols walking past a few feet away. Then we got an

order to go back to Colleville, so we faced the terrifying

railway walk again. That was where my friend Basil Aimers

was killed."

The Odon, so hard to cross with artillery and tanks, is now

a tiny trickle, but with steep, densely thicketed sides.

More men died crossing this stream in July 1944 than

crossing the Rhine. Throughout these advances, the goal was

the ridge of land between the rivers Odon and Orne. Now we

drive there and park near a memorial to the 43rd Wessex

Division. This time, unlike that summer's day when I was 13,

I get out of the car.

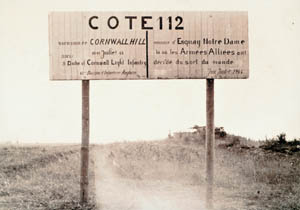

Hill 112 - its height in metres above sea level - is

nondescript as a topographical feature. But in July 1944,

this windswept mound was of enormous tactical importance,

with its wide views in every direction, especially towards

Carpiquet airfield and heavily fortified Caen. Field Marshal

Rommel declared: "He who controls Hill 112, controls

Normandy." One of Operation Jupiter's goals was to take the

hill at any cost.

The attack began before dawn on July 10. Unshaven and

exhausted after two sleepless nights, my father and his

colleagues watched the battle's early stages from Fontaine

Etoupefour. My father was with his Commanding Officer when

Brigadier Essame ordered the 5th Battalion DCLI to join the

attack.

"It was immediately obvious that this was to be a tough

assignment," says my father. "The Brigadier made no

attempt to disguise the danger." Despite Allied air

supremacy, the plan was to use infantry and artillery rather

than

air bombardment. At 8.30pm, the 5th DCLI started to advance,

under smoke, towards enemy tanks that were dug in

on the crest.

"Our own tanks hadn't arrived in time, and the infantry were

very vulnerable. Within minutes, machine-gun fire had killed

nearly all of B Company. Mortar bombs and shells were

exploding all around us. We found we couldn't dig proper

ditches through the tangled tree roots. When it got dark,

the situation became even more confused. We lost touch with

C Company for several hours. We were completely outnumbered,

and the German attacks were relentless and overwhelming. We

had to fight at close quarters, hand to hand. Everywhere,

men were lying wounded or dying. It was a terrifying night."

The fighting continued all night and through the next day.

For his conduct, my father was awarded the Military Cross,

but, with typical reticence, all he will say today is that

he was far less deserving than others in his battalion.

During the chaos, an unauthorised order to withdraw -

possibly of enemy origin - lost the battalion hard-earned

ground. Communication lines had been cut, and the soldiers

were exhausted, having not slept for three nights. By 3pm,

only one senior officer - a major - was still alive. He made

the difficult decision - risking a court martial - to

withdraw without orders, before the rest of the battalion

was annihilated.

"I lost many friends on Hill 112," my father says quietly.

"We had been training together for four years, but none of

us ever anticipated such heavy casualties." He stands

silently, his face sombre, but his bearing still upright.

All around stretches a tranquil landscape, dotted with farms

and orchards.

Hill 112 was never captured - the Germans held it until they

retreated in early August. Later, when my father's battalion

returned to the hill, they found bodies heaped around

partly-dug trenches, scattered across cornfields, and

clogging the River Odon. Hill 112 was never captured - the Germans held it until they

retreated in early August. Later, when my father's battalion

returned to the hill, they found bodies heaped around

partly-dug trenches, scattered across cornfields, and

clogging the River Odon.

On the 60th anniversary of the battle, my father will be

conducting the Fauré Requiem at the Royal Albert Hall. Some

of his thoughts, of course, will be for the music, but most,

I suspect, will drift back to friends and friendships he

still treasures, and to lives cut short almost a lifetime

ago in a tiny corner of Normandy that the French - in

tribute to the men of the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry

- have, for 60 years, called Cornwall Hill.

Normandy basics

Getting there

P&O Ferries (08705 202020; www.poferries.com) runs ferries

from Portsmouth to Cherbourg and Le Havre from about £180

for a car, driver and passenger. Brittany Ferries (0870 536

0360; www.brittany-ferries.co.uk) and Condor Ferries (0845

345 2000; www.condorferries.co.uk) have services from

Portsmouth to Caen and Cherbourg, and from Poole to

Cherbourg. Prices vary according to sailing and time of

year.

First published by the Telegraph

©SarahShuckburgh |