|

A Magical Road Trip into the Unfamiliar

Southern Tunisia

by Sarah Shuckburgh

Southern Tunisia offers the chance to experience ways of life that have remained

unchanged for centuries, says Sarah Shuckburgh

On our road trip through southern Tunisia, we drove through

extraordinary landscapes – stony desert, rugged mountains,

sand dunes, shimmering salt flats, wind-sculpted rocks,

fertile oases. We passed remote homesteads with palm-frond

roofs, and stopped at roadside shacks selling spicy stews or

sweet pastries. In isolated villages we glimpsed ways of

life unchanged for centuries - turbaned men in billowing

white jellabahs, riding horses with embroidered and tasseled

harnesses; veiled women with tattooed faces; souks selling

dates, pomegranates, spices and garish pottery; muezzin

calls to prayer; and everywhere a smiling hospitality which

made us ashamed of our British reserve - “Vous êtes le

bienvenu chez moi comme je le serais chez vous”. You are as

welcome in my home as I would be in your home.

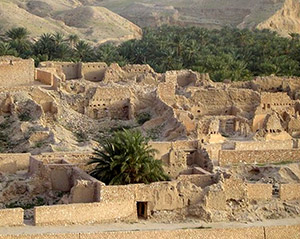

The Ksour region of southern Tunisia is remote, arid, craggy

and fascinating. In this parched terrain, harvests are rare,

and for centuries nomadic tribesmen have protected their

precious stores of grain and olives in communal ksour. The Ksour region of southern Tunisia is remote, arid, craggy

and fascinating. In this parched terrain, harvests are rare,

and for centuries nomadic tribesmen have protected their

precious stores of grain and olives in communal ksour.

Ksar Ouled Soltane doesn’t look like much from the outside –

a high-walled, windowless compound of tawny mud, next to a

hilltop mosque. But inside is a magnificent four-storey

fortified granary, with one of its two courtyards dating

from the 15th century – now a UNESCO site. A young guide

told us that members of his tribe still use the Ksar for

weekly prayers, community meetings and festivals. Each

barrel-vaulted storeroom, or ghorfa, is about eight feet

high and up to 30 feet deep; some still have ancient

palm-wood doors with hefty peg-and-hole locks. Inside, the

clay and gypsum walls are decorated with hand and

footprints, family names, holy eyes and fish, and messages

to Allah.

Ksar Hallouf is an even older granary, dating from the 13th

century. In one cool, dark ghorfa, a yellow-toothed

caretaker showed us a centuries-old oil press where, in his

father’s day, a donkey still pulled a circular boulder to

crush palm-frond bags of olives. In an even darker inner

cave, a giant palm trunk once pressed piles of palm-frond

filters, wedged between stones, and oil oozed into a clay

pit. Ksar Hallouf is an even older granary, dating from the 13th

century. In one cool, dark ghorfa, a yellow-toothed

caretaker showed us a centuries-old oil press where, in his

father’s day, a donkey still pulled a circular boulder to

crush palm-frond bags of olives. In an even darker inner

cave, a giant palm trunk once pressed piles of palm-frond

filters, wedged between stones, and oil oozed into a clay

pit.

Southern Tunisia’s steep escarpments are dotted with caves

where Berbers have lived since the 11th century, when Arabs

destroyed their lowland villages and farms. After a

delicious morning snack of ftair, a sweet fritter, we

visited Chenini, where 500 villagers still live in caves

burrowed into the craggy cliff face. A youth in a blue

turban and baggy trousers proposed himself as our guide.

Like many local boys, Nagi had spent several years selling

newspapers in Tunis, but now he had returned to look after

his grandmother, and, he explained, to help preserve

traditional customs and the Berber language which locals

still speak.

He took us first to the village cemetery, each rocky grave

marked with small standing stones – two for a man, and three

for a woman. Nearby, in a cave-mosque, lie the tombs of the

local marabout saint, and of the Seven Sleepers - imprisoned

Christians who miraculously grew to four meters tall, awoke

after four centuries, and died (again) as Muslim converts.

We followed Nagi up steep clay steps and along narrow paths

to Chenini’s cave-homes, which are constructed in tiers

following the geological strata of the cliff. We ducked

through a low archway to a small whitewashed courtyard,

where his 70-year-old grandmother sat at her loom. She was a

startling-looking crone with purple tattoos on nose and

chin, colourful clothes and clanking jewellery. Beyond her,

the family ghar had been burrowed into the hillside - cool

in summer and warm in winter. A separate cave served as a

kitchen, with an ancient electric fridge.

At lunchtime, Nagi obligingly yelled to someone far below,

and we stumbled down eight storeys of steep, earth steps,

through a series of caves, to a burrowed-out café with two

tables. As we ate chorba (spicy soup) and brik à l’oeuf (a

crispy pastry envelope containing a fried egg) Nagi tucked

into chicken and chips and asked if we had any Wayne Rooney

souvenirs.

Driving northwest, we passed more troglodyte villages – some

abandoned, a scatter of dark holes in a pink craggy

hillside. Blank-walled granary fortresses stood alone,

impregnable in the stony desert. In the distance, a skyline

of sharp peaks loomed. A plump grey jerboa scuttled across

the road. Sheep and black goats grazed on dry scrub by a

long-dry oued, watched by a small child. As we gazed back

towards the glittering Mediterranean, a convoy of 4x4s

roared past, whisking holidaymakers from coastal resorts on

a ‘safari’. Driving northwest, we passed more troglodyte villages – some

abandoned, a scatter of dark holes in a pink craggy

hillside. Blank-walled granary fortresses stood alone,

impregnable in the stony desert. In the distance, a skyline

of sharp peaks loomed. A plump grey jerboa scuttled across

the road. Sheep and black goats grazed on dry scrub by a

long-dry oued, watched by a small child. As we gazed back

towards the glittering Mediterranean, a convoy of 4x4s

roared past, whisking holidaymakers from coastal resorts on

a ‘safari’.

The troglodyte settlement of Matmata bustles with tourists

and touts. Here 100 cave dwellings survive, some dating –

incredibly - from the 4th century BC. Each consists of a

large circular pit, 30 feet deep, reached by a rope ladder

or earth ramp, with tunnel-like underground rooms leading

off it. Many are now restaurants or hotels, and we had lunch

in one – chakchouka (chickpea stew topped with a fried egg).

As we drove west, the stony hamada desert gave way to the

erg – pale, ridged sand, scattered with grey-green tufts. To

the north rose the dramatic peaks of Jebel Tebaga. The road

was dead straight, and utterly empty. Discarded tyres were

piled at the roadside like postmodern art installations.

Mirages appeared and evaporated. A dust devil created a

whirlwind of sand. Camels stalked slowly across the

sand-strewn road – haughty, languid, heads held high.

In Douz, palm frond fences attempt to hold back the Sahara,

and locals are wrapped in hooded cloaks against blown sand.

At the Musée du Sahara, a guide explained nomadic traditions

of swaddling bands, tattoos and the camel-hair burnouse.

Bedouin brides wear black embroidered robes, and ride a

camel pulled by a man who must be called Ali or Mohammed,

and accompanied by a child to ensure fertility. The bride is

concealed by a palanquin, with only her right hand showing -

the hand of Fatima. Strict rules once governed nomadic life

– a curtain in the tent separated men and visitors from

women and children, and the wife communicated with her

husband by banging a spoon on a wooden bowl, so that her

voice would not be heard. Our guide said that he now lives

in the town, but, like everyone he knows, he and his family

return to the desert every year, to spend several weeks in a

traditional Bedouin tent. In Douz, palm frond fences attempt to hold back the Sahara,

and locals are wrapped in hooded cloaks against blown sand.

At the Musée du Sahara, a guide explained nomadic traditions

of swaddling bands, tattoos and the camel-hair burnouse.

Bedouin brides wear black embroidered robes, and ride a

camel pulled by a man who must be called Ali or Mohammed,

and accompanied by a child to ensure fertility. The bride is

concealed by a palanquin, with only her right hand showing -

the hand of Fatima. Strict rules once governed nomadic life

– a curtain in the tent separated men and visitors from

women and children, and the wife communicated with her

husband by banging a spoon on a wooden bowl, so that her

voice would not be heard. Our guide said that he now lives

in the town, but, like everyone he knows, he and his family

return to the desert every year, to spend several weeks in a

traditional Bedouin tent.

Passing Kebili, where black faces are a legacy of a

1000-year slave trade with Sudan, we reached the mesmerising

Chott el Jerid salt flats, a vast, blinding landscape,

dazzlingly white with glints of pink, purple, grey and blue.

In the middle of this glistening, silent moonscape, we

stopped at a shack selling wind-eroded quartz sandroses, and

drank sweet mint tea from grimy glasses. Passing Kebili, where black faces are a legacy of a

1000-year slave trade with Sudan, we reached the mesmerising

Chott el Jerid salt flats, a vast, blinding landscape,

dazzlingly white with glints of pink, purple, grey and blue.

In the middle of this glistening, silent moonscape, we

stopped at a shack selling wind-eroded quartz sandroses, and

drank sweet mint tea from grimy glasses.

Beyond the salty chott, lies the oasis town of Tozeur, with

its matchless 14th-century medina – narrow alleys of

yellowish brick, doors decorated with studded nails, women

veiled in black with a blue stripe denoting their marital

status. The lush oasis has irrigation channels designed in

the 13th century. Here, under vibrant bougainvillea, on a

carpet of fallen pomegranates, we enjoyed plump, sweet

deglet annour ‘finger of light’ dates, from some of Tozeur’s

200,000 palms. Beyond the salty chott, lies the oasis town of Tozeur, with

its matchless 14th-century medina – narrow alleys of

yellowish brick, doors decorated with studded nails, women

veiled in black with a blue stripe denoting their marital

status. The lush oasis has irrigation channels designed in

the 13th century. Here, under vibrant bougainvillea, on a

carpet of fallen pomegranates, we enjoyed plump, sweet

deglet annour ‘finger of light’ dates, from some of Tozeur’s

200,000 palms.

We drove on across another shimmering chott towards red

mountains with knife-edge peaks and corrugated ridges. The

remote oasis town of Tamerza is ringed by knobbly hills of

pale terracotta, with wind-gouged hollows and gunnels,

scrunched, crumpled, pleated and gathered. Almost on the

border with Algeria, the tiny village of Midès is

spectacularly perched on a precipitous outcrop, surrounded

by narrow crumbling canyons. As the sun set, each fold in

the mountain range turned a darker grey, and the strata in

the gorge below glowed red and gold. We drove on across another shimmering chott towards red

mountains with knife-edge peaks and corrugated ridges. The

remote oasis town of Tamerza is ringed by knobbly hills of

pale terracotta, with wind-gouged hollows and gunnels,

scrunched, crumpled, pleated and gathered. Almost on the

border with Algeria, the tiny village of Midès is

spectacularly perched on a precipitous outcrop, surrounded

by narrow crumbling canyons. As the sun set, each fold in

the mountain range turned a darker grey, and the strata in

the gorge below glowed red and gold.

As we headed back towards Djerba, we remembered arid hamada,

windswept erg, glistening chott and jebel peaks. We recalled

vaulted ghorfa in baked-mud ksour, and windowless ghar

dwellings. We pictured men in billowing jellabah or hooded

burnouse, and women in fluttering sifsari. We remembered

delicious meals of spicy chorba and chakchouka, crispy brik,

honeyed ftair and succulent deglet annour. And we felt

pleased to have learnt the Arabic words for the unfamiliar

and magical delights of southern Tunisia.

THE INSIDE TRACK THE INSIDE TRACK

-

Go between the end of September and May, to avoid searing

summer heat.

-

Fly to Djerba and hire a car there for this road trip.

-

Roads in southern Tunisia are empty and well maintained,

with Tarmac surfaces. Sarah hired a regular car, but if you

want to drive further into the desert you will need a 4x4

vehicle.

-

Few in southern Tunisia speak English, so take a French or

Arabic phrase book.

WHAT TO BRING HOME

Delicious deglet annour dates, woven rugs, painted pottery,

brown quartz sandroses, and, from Douz, desert slippers (chaussures

sahariennes).

WHAT TO AVOID

-

Organized ‘desert safaris’ sally forth from coastal hotels

in convoys of 4x4s. As they roar past, you’ll feel very glad

not to be on one.

-

In Matmata, say “No” to the touts who vie with each other to

escort you to the cave where Star Wars was filmed, or to the

museum, charging exorbitant prices. The Star Wars hotel is

called Sidi Driss (entry free); the small cave museum is

interesting and is easy to find. Entry costs about £1.50,

and the tout-guides are not allowed in.

-

To avoid running out of petrol, make sure you fill up the

tank whenever you see a petrol station. In remote villages,

ask locals and a young lad will appear with a plastic

container of petrol.

First published by the Telegraph

©SarahShuckburgh

|